Feb 2013

Ridges and Bumps

February 2013 Filed in: Lumps and Bumps | Human Landscapes

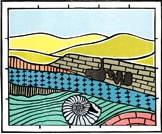

Strip Lynchets at Coombe Hill, Wooton-Under-Edge, Gloucestershire. Photo credit: Synwell / Foter.com / CC BY-NC-ND

As January passes into February, halfway from winter solstice to spring but still the coldest part of the year, it often feels as if it is a distinct season of its own. With low grass in the fields, a touch of frost or a light dusting of snow can reveal a swarm of slumbering lumps, bumps and hummocks of every form, suddenly apparent in a landscape sculpted by the long shadows of the low sun.

Despite appearances, many of these undulations, earthen ripples and waves across the landscape, are not defensive earthworks, ramparts or relics of long-forgotten battles, but evidence of our ancestors’ struggle with the land itself – the remains of various ancient methods of farming – while some are the outcome of nothing more violent than the gradual creep of soil down a hill, occasionally exacerbated by the frolicking trot of sheep.

The most marked features are those shown on Ordnance Survey maps as ‘Strip Lynchets’, the consequence of ploughing along the contours of slopes to create a flat area for crops, as practised in medieval and, occasionally, even earlier times. Dorset and Wiltshire have the best examples – below the Ridgeway near Bishopstone in North Wiltshire and near the village of Loders near Bridport, where giant stair-flights climb the slope; it’s not for nothing that ‘risers’ and ‘treads’ have crept into the terminology of strip lynchets to describe the relevant parts. Further north, at Conistone in Upper Wharfedale and Hall Garth, near Great Musgrave in Cumbria, the effect is gentler, but just as striking.

On more level ground, a pattern of regular undulation can reveal another medieval farming practice – ridge and furrow. Vast open fields were cultivated in furlong (literally furrow-long) strips by tenant subsistence farmers. Working clockwise around their strip, their ploughs turned the sod inward, building up a shallow ridge at the centre of their strip and leaving furrows along the long edges. Hauled by a team of eight oxen, the turning circle in the headland was difficult to achieve without curving slightly to the left at the end of each furlong and a shallow reverse-S or C form to the ridge can often be detected.

In the angular light cast on a February day, far subtler features can be discovered. Thin bands known as terracettes – but sometimes called catsteps or sheep tracks – are formed by soil creeping down steep slopes over the years, a result of repeated saturation and drying. Where bare sedimentary rock is exposed, a light fall of snow might pick out its bedding planes, revealing a succession of sea beds over millions of years or even, on red sandstones, the swash of a desert dune – a geological comfort for the middle of winter.

Comments