Britain Beneath Our Feet

Transcript of a talk given at Hollow Ponds, near Whipp’s Cross, as part of the London Roam festival.

Hello I’m Ian Vince and I’m here to talk to you about London - another London: this one - just a different face of the one you are used to seeing: the one beneath the wheels of this strange little van.

I’m here because I wrote a book called The Lie of the Land, which has just come out and which styles itself as an under-the-field guide to the British landscape. In a nutshell, I am your geology robot - I read geology books so you don’t have to: I then filter all this twisted knowledge through my incumbent ignorance and present you something you may even be able to read with a hangover.

Even if you strip away all the buildings, the park benches, the ponds, the tarmac and grime - all the stuff that millions of years in the future will end up as part of a 2 centimetre layer of compressed Oyster cards, copies of Metro and come-ons from call-box prostitutes - if you strip all of that away, you’re just left with what nature deposited here - the countryside, of which there have been many different types in history and prehistory and all of these have a bearing on the underlying reality of London.

Because, funnily enough, it wasn’t always like this - the ground deep, deep beneath your feet - well over a kilometre down in fact - started out near the South Pole and has spent from 5 to 600 million years making its way here. Other parts of the country - in particular the far north of Scotland are even older - up to 3 billion years old in fact.

Originally I was going to talk to you about all those three billion years. Three billion is a bit of a bankers-bonus kind of number. Even when we’re used to seeing these astronomically huge figures as part of our 24-7 culture of debt, doubt and worry - something I’ve decided to call permageddon. But I thought I’d better find an accessible way of looking at it so I worked out a way of demonstrating how deep the time scale goes.

So here it is

If I say that my talk starts in the present day, now, and finishes 3 billion years in the past and all Britain’s geology can be represented in one hour. At that scale, every second I talk is the equivalent of a million years, which is neat. The problem with talking to you for an hour, peeling off the events as they occur, is that I would be a raving motor-mouth for about nine or ten minutes and find it hard to keep up, after which the silences………

would become… progressively……… more and more…………… uncomfortable. So much less is known the further back we go.

But it’s useful just to illustrate - we are at around a minute from when I clicked my fingers - a minute and five seconds to be precise - 65 seconds or million years ago a giant asteroid hit the earth - we know this because there’s a crater off the Yucatan peninsula in the Gulf of Mexico and a widespread super-thin layer of ash and an element found in relative abundance in meteorites, but thinly spread on Earth, Iridium..

As far as scientists have been able to tell, Bruce Willis was not involved in any way, but that asteroid, along with some other things, wiped out all the dinosaurs. We think of dinosaurs roaming the earth as ancient history and they are but, relatively speaking, they were here right up to the last minute.

Mind you having said that, they only arrived three minutes before along with the Ammonites who - like the dinosaurs - rapidly evolved into thousands of species in very short order and also took that biodiversity down the very same evolutionary plug-hole in the Gulf of Mexico.

If I started my million year a second journey at the very start of this talk, we’d have just passed the point in time which signalled the start of the ammonites and the dinosaurs. So you can see that the deep history of these islands is mind-bogglingly long.

That’s the beauty of Britain, though. A cynic would say that our best bits are all in our history, but I look at the whole country as somewhere that’s infinitely more interesting the longer you look at it. A couple of years ago, I set off with two friends to cross the country from England’s most easterly point at Lowestoft to it’s most westerly at Lands End in - of all things - an electric milk float. What we all found out was that at the speed of a cantering horse, this country is fascinating. You hear whole bird songs, notice wildlife you would normally just pass by and, despite your slow progress spend most of your time wanting to stop more. It was on that journey - for another book called unsurprisingly, Three Men in a Float, that the idea of exploring the countryside really kicked off for me

Anyway, before I get carried away, that’s the demonstration of geological time over - I’m 200 million years in and several hundred metres underground but I should stop now for all of those reasons I’ve outlined.

Instead, I wanted to start here and dig under the subsoil and crap, and talk a little about the most important underground thing in London - the stuff you are standing on (indirectly, at least) right now.

Like a lot of London, here it’s under about 15 to 20 feet of sand and gravel left here relatively recently. In the City, you’d have to dig through about 20 feet of archaeology before you even got to that - here it’s much less. Under all of that lies London Clay. It is a stiff, bluish clay that weathers to a warm brown and bakes into a nice brick - a nice brick that has built most of London. That’s the most obvious expression of the local geology - piled up in neat rows with sash windows in them - the clay is responsible for the look of wide areas of the capital.

There are fossils in it - quite a lot, in fact. It is even better for fossils than a museum gift shop, except there are no ammonites or dinosaurs. Its around fifty million years old by which time anything in the remotest bit Jurassic Park had gone, except the environment. Among the fossils, there are parrots, ibises and relatives of tropicbirds. Turtles and tortoises, alligators and crocodiles, sharks and fish, crustaceans, the ancestor of the horse and a mammal that has many similarities to a hippo - though not related. Conditions are on the luxury end of hospitable.

The clay was laid down in up to 600 feet of water, though land would have been close at hand - probably to the west where there would have been a lush forest - think mangrove swamp in Madagascar or Indonesia. In terms of plants, hundreds of species have been found in the clay, among them a lot of Nipa palm - a plant that still grows today in Singapore, Bangladesh and the rest of southern asia, as well as northern Australia.

It would have been waterlogged mud at first, but the water has been squeezed out by the pressure of having what is now London on top of it. The clay is only about 60 or 70 feet thick in the centre of town, but it’s probably a couple of hundred feet here.

It turns out that it is fortunate for London that it has London Clay.

As mentioned already it’s good for bricks, but it isn’t really stable enough for building particularly tall buildings. But it is excellent for burrowing through and, indeed most tube tunnels pass through it.

But it is terrible for agriculture. An 1807 report by the Board of Agriculture mentioned that:

"ploughing it up where it lies so near the surface as to be accessible to the plough is injurious to the surface soil and future crops. In Middlesex it is called 'ploughing up poison'"

Elsewhere in Britain it was just as warm - even as far north as Skye, but there were even more exotic occurrences. There were huge volcanoes in the North Western corner of Britain as the Atlantic Ocean began its most violent phase of formation. 700,000 square miles of runny lava just poured up out of the ground through fissures to create an enormous plateau - now largely under the Atlantic, we see a tiny part of it at the Giant’s Causeway in Northern Ireland. Eventually the brew of lava changed over time and became thick enough to form shield volcanoes.

The eruptions in Iceland this year are actually part of the same thing - the after-dinner belches that follow the main event.

Iceland, Eyjafjallajökull - May 1st and 2nd, 2010 from Sean Stiegemeier on Vimeo.

Those fireworks have actually been going on for around 63 million years, hot on the tails of the last dinosaurs. They are a result of all kinds of tensions and movements in the earth. Not only was the Atlantic rifting and ripping itself into a proper ocean - putting space between Greenland and Scotland - but also New England and what I suppose I could call Old England - because we were joined at the hip until a hundred or so million years ago. Not only was that happening, which I think you’ll agree is enough to keep us interested, but Africa was pushing into the bottom of Europe and effectively bulldozing the Alps out of the rapidly closing ocean between. But that bulldozing, which pushed the layers of rock under the ocean up into something like a ruck in a rug, then pushed the ruck over and pressed more rucks into the ruck until all the folds were themselves the venue for further folds and everything became completely rucked up. All of that had outer ripples. And we are on one them here.

You might think you’re in a strange Welsh Van, just north of Whipp’s Cross Hospital in London, but I can tell you that you are actually in the foothills of the Alps.

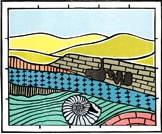

We’re standing on a depression - geologists call it a syncline, but basin is friendlier and does the job better I think. Unsurprisingly it’s called the London Basin and it’s where the rocks underneath us - which were horizontal when they were deposited - have been buckled into a very shallow bowl shape.

Although the lie of the land - the topography of an area - doesn’t always follow the geology in an obvious way, you can get a sense of that bowl shape standing in Greenwich Park at the old observatory and looking North over the City.

The limbs of the fold of that basin spread to the north where they form the Chilterns and to the south where they form the North Downs. Geologists call these beds of rock that are arched or domed upwards anticlines and these anticlines in particular allow the beds of rock deep beneath the London Clay to outcrop at the surface.

The most distinctive of these and our next stop down is the chalk. A bright white rock familiar to everyone - it was made when almost the whole of Britain was covered by a warm tropical sea - a cerulean blue which, if I’m pushed, I describe as being very much like the Caribbean today. I struggle with that because we know of nowhere in the world where chalk is being deposited in the way it was during a period geologists call the cretaceous - when for 10s of millions of years the same conditions of paradise endured. Chalk is a kind of limestone which, unlike all the others reaches a purity approaching 100%. It’s made of billions upon billions of tiny structures called coccoliths, which are shed by microscopically small algae - the one that form blooms in hot summers. Under a microscope these coccoliths look like the tiniest white hubcaps. If you don’t have a microscope you can probably look at more of them than there are stars in the universe by staring at the White Cliffs of Dover.

Under London, these tiny hubcaps form a layer about 660 feet thick. The sea went as far north as the Pennines

If we drill down further we eventually get under the chalk and a time before the chalk sea arrived. There’s a thin section of Jurassic limestones of the sort that Dorset and the Midlands are made of. Any land - and parts of NE London may well have been above the water - as under all the rocks of a trifling age of a couple of hundred million years lies an ancient core of an even older microcontinent called Avalonia. Around East Anglia and NE London, North Kent across the channel to Central Europe, the crust is 10 km thicker than elsewhere in England. It used to be called the London-Bohemia Island, which I always thought was just off Dean Street, but now goes by the name of the London Brabant Massif - which sounds like an industrial hardcore club act.

I then went on to talk about the rocks of the Devonian and Silurian, before a little diversion on the subject of Avalonia - the micro-continent that spent the best part of 600 million years ploughing its way here from the Antarctic Circle.

Keep an eye on this page and the British Landscape Club home page for more events coming soon.

The British Landscape Club