Setting Your Boundaries

There are hundreds of miles of Bronze Age dykes in Britain, although not many of them are as impressive as the deep ditch and high rampart of Bokerley Dyke - a feature which has been shown to predate the Roman occupation. Not much is known of their use as prehistoric borders except that the smaller dykes are believed to be property, rather than territorial, boundaries. Bokerley Dyke’s survival since the Bronze Age is the outcome of its continual use for thousands of years; its upkeep, modification, reiteration and reinvention are all factors in its continued existence in the 21st century and you don’t have to look far to see what an achievement that is.

Looking south from the crown of the dyke, the landscape of East Dorset re-asserts the consensus view of post-war countryside; the familiar layout of arable and dairy, of copses that cling to the hillside and of lone trees apparently stranded at the centre of fields. Tramlines of tractor tracks skirt around each oak or ash like decorative ripples around an island map. In a large field, a solitary tree is often all that is left of a grubbed-up hedge, but here there is a line of them, cast adrift from the field’s edge on a long green island that joins together a pair of Neolithic long barrows.

The barrows are at the northern end of what may turn out to be an even older boundary than Bokerley Dyke. The Dorset Cursus is an enclosed linear earthwork up to 100 metres wide that runs for ten kilometres to the south west – by far the largest of at least 150 similar ancient monuments all over Britain. Nobody knows what purposes they served. Even the most popular theory, that they were processional walkways, doesn’t ring true because their design often included obstacles like boggy valleys and rivers and would make for the most ungraceful procession imaginable.

The location of a cursus often displays a preoccupation with the landscape itself, particularly rivers, but also on the transition from one kind of geology to another. There is some suggestion that they may also be figurative boundaries – perhaps an enclosed limbo between ‘wild’ and ‘domesticated’ land, or as at the Stonehenge cursus, between the landscape of the dead and that of the living. The Dorset Cursus crosses land between tributaries of the Hampshire Avon and those of the Stour, running roughly along the natural spring line.

As far as archeology has been able to tell, the Neolithic in Britain marked the dawn of a spirituality rooted in the relationship between the sky and the land, a practical theology that successfully linked astronomical events to agricultural practise. Our first artificial boundaries may have sought to mark out different kinds of land according to those beliefs, but by the Bronze Age, these sacred lines were dismissed in favour of more earthly divisions.

Comments

Independence or No, Scotland's Singular Past is at the Root of its Unique Appeal

Friday, 19 September, 2014. Filed under: Scotland

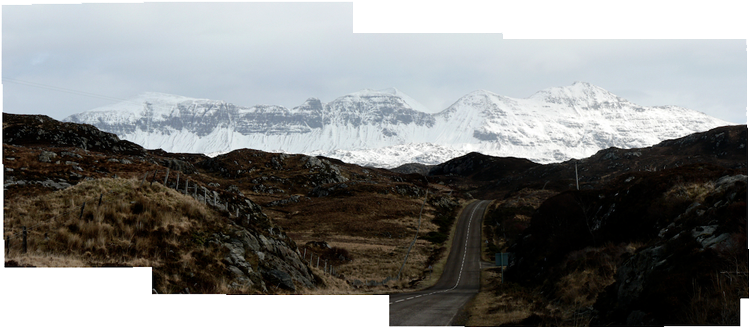

The Road to Lochinver in the Northwest Highlands of Scotland © Ian Vince

The Independence Referendum has ended in a ‘No’ Vote – albeit with a significant minority in favour – but the roots of Scottish independence run deeper than any year-long campaign or generational shift; Scotland’s distinctiveness is built into the very fabric of the country.

While the arguments about independence have always been less about getting rid of the English and more about a detachment from the ‘Westminster Village’ and bringing power closer to home, west of the road that connects Inchnadamph, Stronchrubie and Knockan Crag, a different form of power begins to become apparent. Here lies the basement rock of Britain – a slab of crust two thirds the age of the planet on which the entire edifice of Scotland is presumed to rest.

It’s a distinctive landscape that hints at an ancient independence; before the land that now forms Britain was welded together hundreds of millions of years ago, what lies below Scotland was actually a part of the Canadian Shield – formed deep within the Earth around three billion years ago, these rocks – the Lewisian Gneisses – are exposed here on open rolling moorlands, punctuated by countless lochs, lochans and Scottish puddles with mountains like the sugar-loaf inselberg of Suilven towering above.

The oldest rocks of England, by comparison, are relatively fresh at around 600 million years. What is particularly interesting is that these two landmasses are welded together miles underground along a feature known as the Iapetus Suture which runs roughly along the same track as the 300 year-old Scottish-English border. Iapetus was the father of Atlas, who gave his name to the Atlantic Ocean – the suture is all that is left of the Iapetus Ocean which once divided the proto-American continent of Laurentia with its pre-European counterpart, Avalonia. When the Atlantic opened up, bits of Laurentia were left behind in Scotland and parts of Avalonia ended up across the pond – chiefly parts of Newfoundland and, believe it or not, New England.

We have more in common with far-flung parts of the world than we may know, but places and people close to home can feel distinctly different for good reasons. These are lessons that Westminster seems set to learn.

The Strange Day that a Five-Acre Hole Disappeared

Wednesday, 17 September, 2014. Filed under: Strange Days | Landscapes

In search of Angelina Sedgwicki: A five-acre hole on a Welsh hillside proved surprisingly elusive. ©Ian Vince

On a damp and squally warm Welsh day in late summer, I make my way up a steep track that runs along the edge of an ancient wood. I am in search of something exotic - the distorted fossil of an Angelina Sedgwicki, a half billion-year-old Trilobite a little under two inches in length. The fossil, according to a guide book I had recently uncovered in a secondhand bookshop, is apparently fairly easy to find - perhaps within a quarter of an hour or so of diligent rock splitting in an abandoned quarry on the other side of the hill - a statement I accept completely without question.

The trilobite I am looking for was laid down in mud and then squeezed as if in the jaws of a vice when two continents collided 430 million years ago. It was the same process that contorted muddy shales into the Welsh slate that still roof the Victorian suburbs of industrial English cities and I would apparently discover at least one contorted specimen splitting those slates apart. However, in order to do that, I have to find the quarry first and it seems to be peculiarly elusive for a five acre hole in a Welsh hillside.

Following the directions, I pass through a gate and struggle up a path that runs between ancient dry stone walls carpeted in moss. The wood is musty, its air thick and oppressive and every warm breath is filled with the cloying scent of chlorophyll before a summer storm. My asthmatic wheeze is accompanied up the hill by the nearby whistle and puff of a Welsh steam engine - recently re-purposed from carrying rock to ferrying tourists - which seems strangely apt, as I am the latter in search of the former.

The path levels out for a few yards as it crosses the saddle of the hill, then plunges down the other side towards the meadows of a flood plain. On this side of the hill, the geology of the area suddenly asserts itself on the path’s character. The wall incorporates thick slate within its structure and the footpath becomes strewn with large, loose slates making an unconsolidated scree upon which every footstep is uncertain. I elect to walk down through a stream bed that threads its way from one side of the path to the other, preferring the discomfort of wet feet to a long slide towards certain concussion. This trilobite, I tell myself, had better be worth it.

After ten minutes of alternate squelching, slipping and side-stepping my way to the foot of the hill, I find myself in the corner of a field, the expected location of a quarry which isn’t there. I check the map, read the directions and peer back up into a wild wood of tangled hornbeam and oak. I can just about make out what looks like a face of rock, but it may as well be on the other side of a barbed wire thicket - the wood is utterly impenetrable. A mosquito rasps into my ear, just one of hundreds buzzing around like paparazzi on mopeds circling their quarry, while I completely fail to get near mine. However, a few large boulders of slaty shale have tumbled onto the edge of the meadow and I spend twenty minutes with a hammer and chisel breaking rocks, all to no avail. I eventually give up, down tools and give in to a mind-altering mix of perspiration and disappointment.

I sit on a rock, take stock and try not to think about climbing back up the path. Sitting there in the quiet, I hear an almost metallic, ‘chip, chip’, which is quickly followed by ‘peek, peek’, a sound which has a chalk-squeak-on-a-blackboard quality about it - a grating, citric creak that seems more at home between your teeth than in your ear. Following the sound, my eye is drawn to a flash of short, white tail feathers and a streak of rusty brown. I find my binoculars and after a moment of searching along a branch of hornbeam, I locate the most exotic creature in the woodland, bar none - a Hawfinch. What gives it away, for the two seconds it is in plain view, is its bull-headed appearance and enormous gunmetal blue-grey beak - one field guide calls it a ‘flying pair of nut-crackers’.

The Hawfinch is characterized as being shy but, as it generally spends most of its time in the canopy of mature woodland, elusive would be a better description. After thirty years of looking out for one, this is my first and seeing it for the first time is a spectacular moment of triumph. It flies quickly back into the canopy and is soon lost again. After that, the trilobite is just history.

Bonfire of the Baptist

Wednesday, 17 September, 2014. Filed under: Cornwall | Strange Days

At the end of a long journey into Cornwall, crumpled into a corner of a train, I was longing to get out on the open moor. Aside from the cattle truck stylings of British rail travel, the journey only reinforces the impression that Cornwall is a very long way from anywhere. And, along with the promise of witnessing an event that, though once widespread, only occurs now in Cornwall, it is this remoteness that brings me here.

“Here” turns out to be somewhere between Penzance and Zennor in a field near the hamlet of Boswarthen which is, itself, to be found just off an isolated road north of Madron. Despite the abundance of placenames, each of which sounds like the grave syllables of a mumbled prayer, I am effectively bang-slap in the middle of nowhere.

I’m here for a bonfire, specifically a midsummer’s eve bonfire on top of a hill overlooking Mounts Bay – one of at least half a dozen such events arranged by local Old Cornwall Societies up and down the county. The guiding principle of these societies is to hold on to the old customs and keep them alive for the next generation – a process of ‘gathering the fragments’ of Cornish culture, language and traditions which has steadily grown in popularity over the years. Sure enough, the secluded lane quickly fills with parked cars as organisers and spectators turn up, almost all at once. People of all ages are here, from the local Young Farmers who are having a barbecue in the back of a horse box, to a strong contingent of senior villagers.

“Health and safety would probably want us to put up a barrier around that”, says Roy Matthews, Honorary Chairman of the Madron Old Cornwall Society, waving in the general direction of a 12 foot high pyramid of old pallets and fertiliser bags. “But the thing with a fire is that it’s hot, you see. Nobody’s going to be able to get anywhere near it once it’s lit.”

He goes on to explain some of the history of the bonfires. Thousands of years ago, animal sacrifices would be made on them. “Sometimes, they’d throw the odd criminal on”, says Matthews, with a playful gleam in his eye, “but now we throw a wreath on instead.”

By about 9 pm, around seventy people have crowded into the small field. The air is thick with the smell of the horse box burgers, dozens of conversations have coalesced into a soft murmur, at which point we are handed our photocopied song sheets – along with a steely warning to return them later. We are to be accompanied by the parish priest, the Rev. Tim Hawkins who, rather than appear here in an official capacity, has brought his viola along instead.

At first I mouth the words, like a self-conscious schoolboy in morning assembly, as I don’t wish to appear impolite, but I am eventually swept up in it all - the beautiful location, the camaraderie and the life-affirming spirit of a sing-along at 700 feet. Undaunted by my lack of vocal talent, I join in with Hail to the Homeland and Going Up Camborne Hill, Coming Down and my mind is elevated from its usual default settings. I have become one of them.

As night draws in, and with the final chorus of Trelawney still ringing in my ears, the ceremony begins in earnest with the reading of the prayer – first in Cornish, then English. When the ancient Celts were converted to Christianity, the fires were transformed, with the early Church’s usual resourcefulness, into celebrations of the Feast of St John the Baptist. As a result, every bonfire now has a benediction which includes a couple of priceless puns about “being lighted by Thy grace and fired with Thy love”.

After a brief explanation of the symbolism of the bouquet of herbs that are to be thrown in to the fire – in place of a local ne'er-do-well – and some words from the Master of Ceremonies, a man appears with a bottle of white spirit to set things off in style. It’s only moments before the pyre is blazing furiously away, its wild flames clawing at the inky blue-black sky. For all the layers of ceremony, etiquette, poetry and faith superimposed over the night, the fire itself is the focus and this is as it would have been for our ancestors, a celebration of summer through the building of a simulacrum of the sun itself.

Clinging onto those thoughts, I wind down the narrow lane home. A Cornwall Fire Brigade engine with sirens screaming and blue lights blazing appears from nowhere, heading in the direction of the flames I have left behind. For all the efforts of the organisers, it seems that the wild old and the ordered new Cornwall are yet to be reconciled.

Layby of the Week: Ranmore Common

Friday, 22 August, 2014. Filed under: Landscapes

The North Downs in leafy Surrey are one of the hidden gems of Britain and Ranmore Common, a large tract of woodland west of unfortunately-named Dorking, is one of its lesser known spots, losing all the glory to admittedly glorious Box Hill next door. But this view from the meadow that lies behind the car park on Ranmore Common Road is typical of the kind of vista the North Downs provides in spades. Enjoy the view.

View Larger Map

View Larger Map

Urban Views - Pay and Display of the Day

Friday, 15 August, 2014. Filed under: Urban landscapes

From the people who brought you Layby of the Week. We are proud to announce Pay and Display of the Day* – its urban counterpart.

Today’s entry is the fairly nautical wonder that is Bristol’s Floating Harbour and a view of it from just down the road from St Mary Redcliffe’s Church in Redcliffe Parade car park. Point your pupils at this:

View Larger Map

And if you visit, the Redcliffe Caves are yards away, the church is sublime and Bristol is a beautiful, bustling city.

*Despite the name, they won’t be daily.

Today’s entry is the fairly nautical wonder that is Bristol’s Floating Harbour and a view of it from just down the road from St Mary Redcliffe’s Church in Redcliffe Parade car park. Point your pupils at this:

View Larger Map

And if you visit, the Redcliffe Caves are yards away, the church is sublime and Bristol is a beautiful, bustling city.

*Despite the name, they won’t be daily.

By Eck, Layby of the Week returns

Monday, 28 July, 2014. Filed under: Landscapes

By Loch Eck, to be precise. This five star view, from the beautiful Argyll Forest Park, can be had from one of the most picturesque spots yet revealed to us in our relentless GoogleTrundle around the roads of Britain. It’s not the kind of place you discover by accident on your way to the shops, but if you’re ever in the area, it’s worth at least a thermos of tea and some petticoat tails.

View Larger Map

View Larger Map